a true memoir

just a drop kick from punt road ...

Before the Flood

In a flat sunburnt country with flooding rains and long dusty droughts, things not washed away fade in the sun as much as in the memory.

Priests in black cassocks sway slowly down a long aisle with incense and white lilies. Gravel voices intone earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The boy did not understand but knew to keep quiet. He just wanted to get out of that dull hall they used as a church and kick his little football down the hill.

The hill sloped from a main road down to a creek. South to North. In the wet, mud slipped blackly downhill. The prevailing winds in winter, as he learnt many years later, drive in from the North so that sometimes gravity would more or less be equalised by air pressure. But not all that often. What usually happened was that the ball would bounce and skid and roll to the bottom wing, across the boundary line and into the creek.

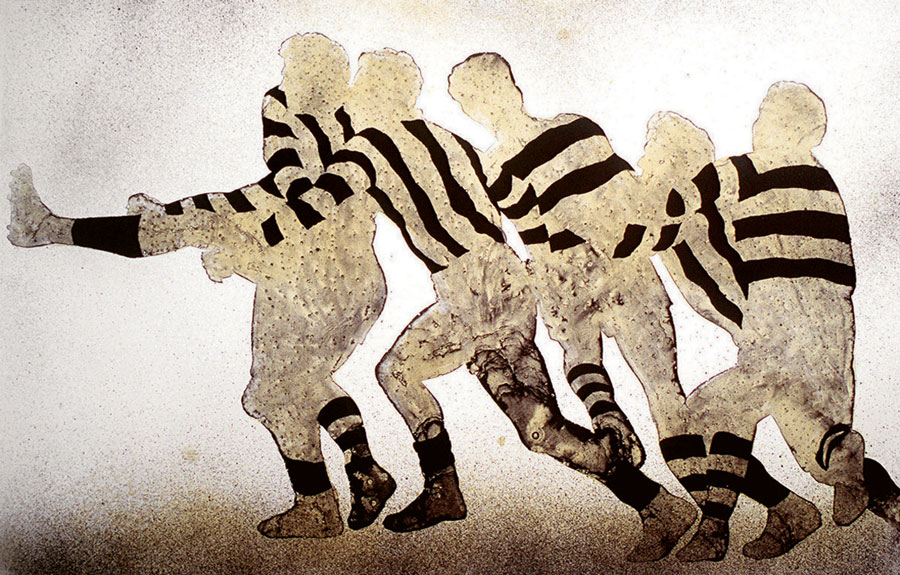

They were told to kick long in those days, short passes were only for rovers pinpointing the full forward, but that steep hill would take over and the ball would bounce free and just roll away with ten or more boys running after it. Running in packs.

He usually played wing, being young and fit. Fast of foot. When they changed ends the wings were supposed to swap over, so in theory he’d get half the game at the bottom of the hill and half at the top. Most of the play was at the bottom, almost none at the top. But Martin Stewart would usually race out to the lower wing whether the team sheet had him there or not. He knew where the ball was going to be and he was a good player, getting six or seven kicks a quarter. Then at the quarter time break he’d refuse to swap over, just stay where he was.

Stewart was the better player so the boy didn’t feel he could tell him what to do. He’d just wander around the empty boundary up that muddy hill calling for the ball but knowing it would never come.

One day his dad got off work and came down to watch them play and he yelled at the boy to go in for ball, go in and get it. But that would mean running down into the pack and breaking all the team rules, which he knew not to do. So he didn't even try to impress his father.

It’s a team game. The team is more important than the individual. Hold your position. Man up. Play in front. Lead to the flanks. Protect the man with the ball. Shepherd. Man up. One handball one kick. Kick it long. Chest marks. Never handball on the back line. Man up.

All that talk of men appealed to the boys, inspired them, mapped out their future for them. It’s edifying to be called a man when you’re fifteen and so self conscious you won’t shower in front of the others, especially with that acne on your back. Sometimes a few girls would come to watch the game and giggle and he often thought one of them was smiling at him. Team mates like Stewart would show off and break all the team rules and chase the ball out of position. Of course they’d usually get it with a high mark or a one-handed pickup, just as the ball was arcing towards his position. The rules were made for the team but the best players could ignore them when it suited. They were playing a different game.

Most of those rules don’t apply any more, this was before the modern game, before the press and the flood and the rotations.

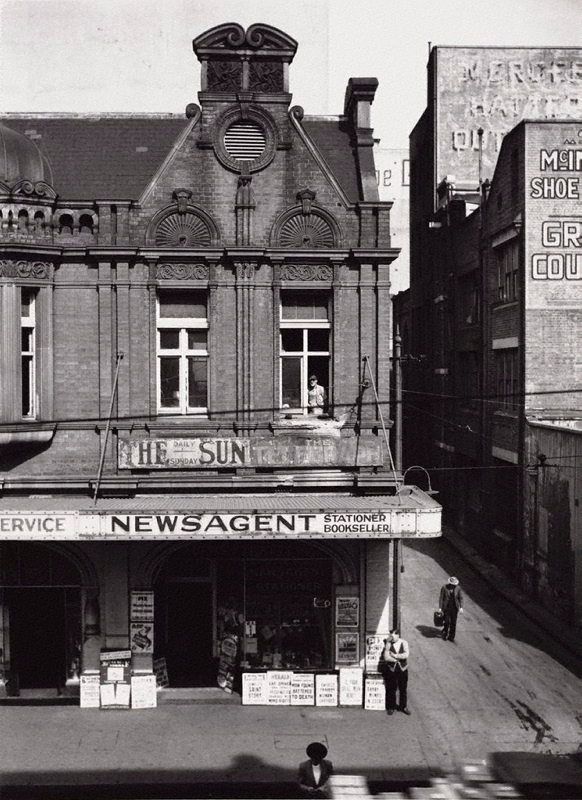

This was when mothers stayed home to cook dinner and hang the washing on the Hills Hoist. When the Hills Hoist was made in Australia, when so much stuff was made in the country that every man had a job and most boys did too. A paper round at least, or Saturday morning at the green grocers unpacking wooden crates and tossing rotten squashed fruit from the bottom of the stack into a forty four gallon drum. Trying not to dry retch. Thankful for the shilling. Men wore hats and women wore floral dresses below the knee. Boys, mostly, wore short pants above the knee.

This was long before television, when the wireless was the only real thing you could call mass media apart from the Saturday matinee. The matinee featured movies like Audie Murphy’s To Hell and Back. There were still lots of war stories around and the radio had Biggles and Hop Harrigan and the Dam Busters. Hop Harrigan was on at breakfast time so the boy could listen while eating Corn Flakes and then pretend to fly to school on his fixed wheel bike, when he wasn’t pretending it was his palomino or piebald pony. Biggles was rather up market from Hop Harrigan because he was English and anyway there were books about him whereas Harrigan was a character in yankee comics. There were books about the Dam Busters too, as well as the greatest film of all time. Two generations later he noticed that the last living Dam Buster had died in New Zealand, in his nineties. And then for the first time he thought differently about those bouncing bombs hitting the dam wall and winning the war for us. Because when they broke the wall they flooded the valleys and drowned all the people and destroyed their towns and farms. But back then no one thought about that, no one mentioned the flood or that the Germans too were victims of the war.

This was an earlier time, a more innocent time.

This was a time of long boring school holidays. Mowing lawns, swatting flies, shifting slowly on sweaty sheets that stuck to your skin on summer nights, listening to far off thunder and waiting sleeplessly for something to break. Not knowing that what was slowly passing would never come again.

This was when people moved out of the inner suburban slums, to be replaced by migrants, wogs, eye-talians. Horses still clattered down morning streets, delivering milk and bread. Cycling to school one morning with a mate, they hitched onto a baker’s cart going up Mont Albert hill. The wooden wheel caught on the bluestone gutter and jolted, the rear door flung itself open and bread and buns and cakes tumbled out onto the street. They shouted to the baker but he didn’t hear them, so they grabbed as much as they could and stuffed their school bags full. They got to school late but didn’t get into trouble because they shared their loot with the whole class.

Even the teacher had a jam bun, and told them to give one to the sole wog boy, Roberto. He’d only been in the country five minutes and couldn’t speak a word of English. He wore sandals even though it was winter, they were the only shoes he had. The teacher yelled at him and he scrambled under the desks with Brother Romulus chasing him with a yard long wooden ruler, swinging it left and right and all the boys ducking, thankful it was Roberto being hunted not them. No one dared stand up for him.

This was when migrants were barely seen in the outer suburbs, still partly orchards with hillsides of blossom in early spring. Before most families had cars and everyone walked to school or the shops, or rode their bikes to the river to swim, or caught a stuttering bus to the city to go to the pictures. His father brought a car home from work one weekend, they were going to drive on holiday to the beach and got up Saturday morning really excited, only to find the driveway was bare and the car had been stolen. They hadn’t even been in it and it had disappeared.

Because no one had a car the team travelled to away matches in a furniture truck owned by one of the fathers, a tough looking wharfie with sideburns and slicked back hair. Everyone would pile into the tray covered with a tarpaulin and roll around laughing on every bend. Laughing on the way to the match but sometimes glum and silent on the way home. It was a way of seeing the city, of getting to places far away from the almost rural valley with it’s new house frames and red brick church. Far away places with English names though in the north were German suburbs like Coburg and Brunswick and Heidelberg. He realised that the world was wider and more mysterious than the family home.

There was a strict pecking order in the back of that truck. Junior players only talked to each other, quietly, but responded quickly if an older boy spoke to them, and laughed loudly when a star said something outrageous. Sometimes the driver tooted the horn and they’d all cheer and whistle and scramble to the tailgate thinking it was a girl. Or hoping it was. Bobby Megna could whistle the best. He was eye-talian but had been fully accepted because he was such a good mark. A good pair of hands. And he kicked goals even from the flank. Although only fifteen he’d already left school and was working in the family butcher shop. One time he missed a match because his uncle was slaughtering a pig and making prosciutto. No one knew what that was but the coach said it was wog bacon. Then he missed several games in a row because he cut off the end of his finger at work. He wasn’t such a great mark after that and the team started losing and missed the finals. The following year Bobby played again on the half forward flank but then cut another finger off and missed the rest of that season.

They said he played again at another club but was past his best, even being picked as 19th or 20th. This was before the bench, before the interchange. If you were 19th or 20th you’d only come on if someone was injured. It was a sort of poisoned chalice, better to be selected in the Seconds and get a full game. Or so they said.

The boy was lucky in those years, he always played Firsts. Usually on the wing. The number they gave him for his mum to sew on his jumper became his favourite. Any league player with the same number would be his favourite too. One Saturday the tarpaulin-covered truck drove into Fitzroy and they played Preston at the old Brunswick Street oval, still at that time the Maroons home ground. He starred, taking marks, kicking long with the torpedo and short with the stab pass. The ground was flat, the surface smooth. The ball bounced in a straight line. He got more votes than either Stewart or Megna, in fact he was best afield.

It was something he remembered for ever. In fact, when he thought about it years later, he was actually sitting up in the old historic stand watching himself streaming down the wing bouncing the ball and looping it into full forward. There was no hotspot back then, no corridor, no forward press. He could see himself sitting up in the stand better than he could remember the game. Except that they won and he got votes. When he got home his Uncle Lucky asked him how did you go, and when he said he played well and got votes his uncle raised an eyebrow and said how did the team go, emphasising “team.” The team was important Lucky told him, the individual was not.

Rebuked, he never mentioned it again to anyone.

So in time the only person who knew how well he played, the only one to actually see it, was himself. Sitting in the grandstand watching.

In time all these things passed from reality into dream. People bought cars and women went to work. New Australians became real Australians and moved into the suburbs where they built bigger brick houses with double garages. Motor traffic filled the roads and horses were seen no more in the streets. Young Australians stopped going to England by boat and Vietnamese started arriving in their own boats to fill up the West and the South East of the metropolis which itself doubled in size. Eye-talians became Italians and wog became a superfluous term. Greeks and Italians and Yugoslavs were now called Europeans because they were not Asians, everything was changing. Then suddenly there were no more Yugoslavs but Serbs, Croats, Macedonians. Migrants became Asian or black or Muslim. Souvas and kebabs became as common as burgers.

More and more non-English names started playing football. Silvagni, Daicos, Dimattina, Capuano, van der Haar, Jesaulenko, Kekovich. Suburban grounds were converted to soccer pitches. Soccer was renamed football and lots of people got confused and lost their ethnic origins. Most grounds got big lights so the boys didn’t have to train in the dark. They started to put padding around the goal posts. Years before legends had grown around tough guys like Tony Pannetta who ran so hard to stop a goal he smashed into the post and cracked it. Everything was changing. First uni students and then young professionals began their move into the inner suburbs, renting then buying and renovating houses that only a few years earlier were being demolished as slums. It was hard to find cheap accommodation near a tram line but dead easy to buy a cappuccino.

He moved house a lot and stopped playing. Sometimes he went to the ‘G for the last quarter when they opened the gates for free. That had been a long tradition dating from the Depression, or so he’d been told. Having a kick on the ground after the game was nearly as good as the real thing and you’d see a lot of champions taking screamers. Occasionally he’d see a great from the early years or an old mate now thicker below and thinner up top.

Outside the stadium one September he bumped into Georgie Despard who could drop-kick with both feet but never played in the team because he would’t train. Sometimes he’d come down to watch and give advice which everyone ignored. His arms covered in tattoos and with a crooked grin showing just a few teeth he now told his story of tech school, Turana, youth detention and jail. Two wives and three kids and five years in a Queensland mental institution. What was best remembered about George was the drawings of Cowboys and Indians with horses that looked real. Palominos and piebalds. Georgie was allowed to draw because he couldn’t read. Still can’t he laughed.

He met Roberto again as a man, an accountant with a silver BMW. A big house and two daughters. He’d played neither soccer nor football but went to uni and made a success of himself. Investments. He met Pannetta at the Market and they discussed the old days in tentative terms, neither of them sure how much was really remembered and how much was wishful thinking. He never met Bobby Megna again but often wondered how many fingers he might now have.

One day he drove from Punt Road past the old ground and it wasn’t even there. The hill had been levelled, the creek filled in and the park landscaped with mature blue gums and big rocks from a far away desert and clumps of native grasses. Women in four wheel drives queued at the lights and tooted at men in Mercedes and Lexus sedans who ignored the traffic signals and just drove as if they made up the laws themselves. He sat at the red light obeying the rules and looked across to see no boys playing football, no kids down the creek, no sign of his memories and none of the life that had been there before.

A young woman pushed a pram and walked her dog through the dry grasses and rusty rocks. The dog sniffed around but the baby in the pram never touched the earth and so could not know this land.