I watched from an old upstairs window just straining on tippy toes to see. To see my mother crossing the street way down below.

She said she’d be back soon and the nice wide nurse said that too. She’ll be back soon. She’s not leaving, don’t worry, just going to get something. Be back soon. But she didn’t even look up as she walked away

I remember too a dark haired and pretty woman, who might have been my mother, tossing a sheet as she was making the bed, or a table cloth in the mahogany dining room. The light catching the white cloth and shining in her eyes. The ceiling was very high for a little boy to notice but there was a cream round rose made of plaster and the fluttering fabric cast ripples of shadow across it.

The ceiling was very high but little boys are always looking up at the big people around them.

I saw a short art movie years later which contained a scene like this repeated several times the way art movies do. I have no idea whether the scene I remember originated in the movie or in our house, or at another person’s house.

But I know it happened, deep within. When I asked my mother she said I’d had to have my tonsils out. She couldn’t recall tossing the sheet. The doctors also convinced her my feet were turned in and I wouldn’t be able to walk properly.

That was a little while after I’d walked from my grandmother’s house in Richmond to the family bakery one quiet sunny afternoon looking for my dad. Uncle Billy was at the bakery, lounging in the huge gateway where the horses snorted and steamed as they stamped out to deliver bread to the city of Melbourne.

Uncle Billy queried where I was going and how I got there. He was surprised that such a little boy would walk that far west, even to look for his father. He said that Jack wasn’t there, had gone home ages ago. So I went back again, somehow knowing my way through the sunny empty streets. Funny thing that Billy didn’t take me in hand, look after me and make sure I got home safely.

But the doctors, not knowing all this, said I needed callipers so I would not be deformed when I got older. So they fitted me with leg irons held with leather straps and sent me to kindergarten where I couldn’t play with the other children, but stood on a hill of tan bark while they ran and called all around me.

We used to go by tram up Victoria Street, and it seems that Nana, my grandmother named Dulcie, used to take me there with the little girls that lived across the road. Although those girls were older so probably going to the Catholic school next to the kinder. Getting on and off the tram was difficult in the callipers and people kept trying to help me. You poor little boy. This made me angry and I’d push them away, even Nana on the steps of the tram. She’d tell me to hurry up because I was taking too long to get off.

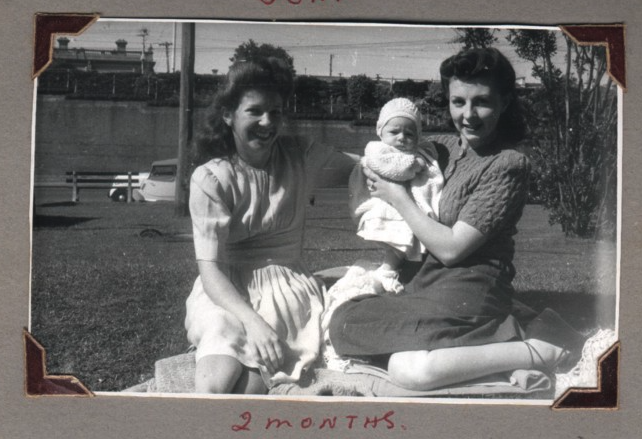

When my mother was diagnosed with cancer at age 92 I asked her about these things. She said “why are you asking me about that, we carried you in our arms!” Of course they did, they carried me when I was a baby, before I could walk, I can’t remember that, being carried in their arms. No more than my boys might remember being carried in mine.

Those art movies I loved in the sixties and seventies often used repetition. The same or similar scene is repeated or perhaps referenced as a stylistic device, giving a sense of rhythm. To reinforce a point or to lead the viewer into thinking of something that is not directly stated. It can be an effective technique when used with restraint and I’m tempted to work it into this narrative. But the world has changed so much, and I’m not sure that anything can be repeated.

In my childhood horses still clattered down the morning streets, delivering milk and bread. Walking with my father one warm evening we saw a pony hitched to a light post. The reins were around the tall pole and the pony stood quietly waiting for its rider. It intrigued me how they’d done this — did some giant lift the creature high in the air and loop the leather over the top of the pole? My father laughed but never explained that the harness actually had two two straps buckled together.

I remember a lot of horses. One huge monster blowing steam from its nostrils, filling the doorway of the stables behind the bakery where the workers fed me lamingtons with sticky chocolate. A row of hansom cabs stood in the middle of Russell Street below the dance studio window. I looked down from there, another big high window from which a little boy watched the world, while one of my sisters practiced at the May Downs School of Dancing.

Our family revolved around these important people like May Downs and Annie Davidson and Jack O’Keefe. Then there was Uncle Jim and Aunty Vera and a whole host of nominal uncles like Frank and Kenny and Billy and Alec, and a range of neighbours that I can’t remember the names of, though I do remember Minnie Harvey.

We used to walk around to Minnie Harvey’s place in the next street, sometimes we’d go down the lane. My mother, my Nana and me. It is always sunny in my memory, with blue skies and bees buzzing amongst Minnie Harvey’s backyard flowers. The gardens in those days were at the back because the front of the house was almost on the street. Minnie was a big woman in a blue and yellow floral dress. She sort of blended with her own garden while they all gossiped about other mothers and I chased the butterflies and bees.

Minnie Harvey was mentioned a lot in our house, my grandmother’s house. I call it hers because my grandfather, Toots, did not seem to be home very much. I remember his hat, and him teaching me to draw a box in perspective, and also a doorway with the door opening inwards. He laughed with satisfaction when I could do it. He tried to teach me to draw a pony, being a racing man. I think that was Toots, but it might have been Uncle Arthur. I know Uncle Arthur played cricket with me in a grassy backyard somewhere while mum visited with Auntie Bertha, a huge woman who took mum in before the war and had been like a mother to her.

That was because mum did not have a mother really, she had a step-mother because her own had died when she was four years old. Or so she told us whenever we’d ask and this always seemed sad and unfair. And I wondered who had carried her in their arms.

Mum had gone to Bertha’s in Carlton after leaving home as a teenager, because she had hit her step mother. That woman, Alma, had been belting and mistreating mum and her crippled sister Norma since they were little children. Finally mum hit her back and was told she’d have to leave, and even her father didn’t defend her. She met Bertha in a Fitzroy factory and moved in with her, and managed to get Norma to move there too.

This seems to have been a turning point in my mother’s life, about 1937, before she met my father, when she was still a kid really, finding a job, making a life, moving towards independence, taking responsibility for her little sister and not knowing that war was looming. She had a lot a stories of those years, like going to the footy at Princes Park and yelling out and the woman next to her was yelling too and offered her the shelter of an umbrella and that was Marge Johnston. They became best friends, until Marge died sixty years later.

I remember Marge as a thin quirky woman with a sense of humour. She liked me. Her significance was that she was mum’s friend and that she liked me. She lived in a flat in St Kilda and we went to visit by tram. So bohemian, I knew what that meant even if I didn’t know the word. Marge had two daughters, Coral and Dianne and I fell in love with Dianne because she was pretty and danced at the Tivoli. I met Coral again years later at mum’s ninetieth birthday but never saw Dianne after that day in our backyard when she spun around in a short flared skirt.

Young women in those days were always thin with long hair.

But Minnie Harvey, Auntie Bertha, mum’s step-mother Alma — these were fat women and big presences who dominated whoever was around them. I remember this in contrast to Nana and my own mother, who were small and slight and sort of insignificant in the wider scheme of things. The significant women, the big presences, dominated my childhood — May and Tuppy. Aunty Marie.

But I digress, as one does when memory starts to stir. There’s really not much that you actually remember and even less that you can swear to with certainty. The inner child, that powerful unconscious creature, can access an immense number of hard-wired secret scripts that our external selves see only in dreams, or in vague recollections of a moment, a scent or a fleeting glimpse of something from the corner of an eye. But as you open one door or look in one window, another appears briefly and you start to wonder what’s real and what’s a memory of another memory, that was maybe begun by another person’s words or a photo seen long ago in another house.

You need hard data to be sure of the past, something on paper that someone official has signed or sealed as authentic. But you must ask does the authenticity ring true? Does it confirm the reminiscence or feeling? Then you have to decide whether you want to write a narrative or a factual family history, like a genealogical tree and its roots. No wonder real writers drink a lot and don’t have any friends.

Memory is so selective and always at the beck and call of other powers, like justification, rationalisation or excuse. Perhaps some documentation will refresh this story.

Twenty years ago my sister researched the archives looking for our grandmother. Not Dulcie but Rose, Rose Hubble, mum’s mum, born at the very turn of the century, January 31, 1900 according to her medical records. Born Rose McIntosh. Which immediately raises another story, one we flirted around as kids when we pored over the atlas looking for our ancestral roots in the Scottish highlands

The Davidsons came from Scotland, members of Clan Chattan, Gaelic for cats, who intermarried with the McIntoshes early in the fourteenth century. Important to the story is that the Davidsons were decimated in 1370 at the battle of Invernahavon, in the Scottish highlands, when the McIntoshes led them against the Camerons but the MacPhersons sat out because they felt the Davidsons had insulted them. This tipped the scales against Clan Chattan, those misled cats, and the only Davidsons left were the few who’d stayed at home, unwilling to fight for another family’s honour.

Thus, early in the family history was an alliance with the McIntosh family, pride, insult, petty bickering, betrayal and massacre. The Davidsons virtually disappeared for centuries while the McIntosh clan was later almost wiped out at Culloden. Not exactly illustrious an achievement nor a glorious heritage.

And so much later, in 1943, a distant son of the Davidsons married a daughter of McIntosh as the pattern repeated itself.

- from my dubious memoir “We Carried You In Our Arms” published on Blurb, 2018